Seeing Beyond the Fire: How a Visual Image Moves Us

How a Scene from 12 Years a Slave Shapes the Way I Teach Storytelling

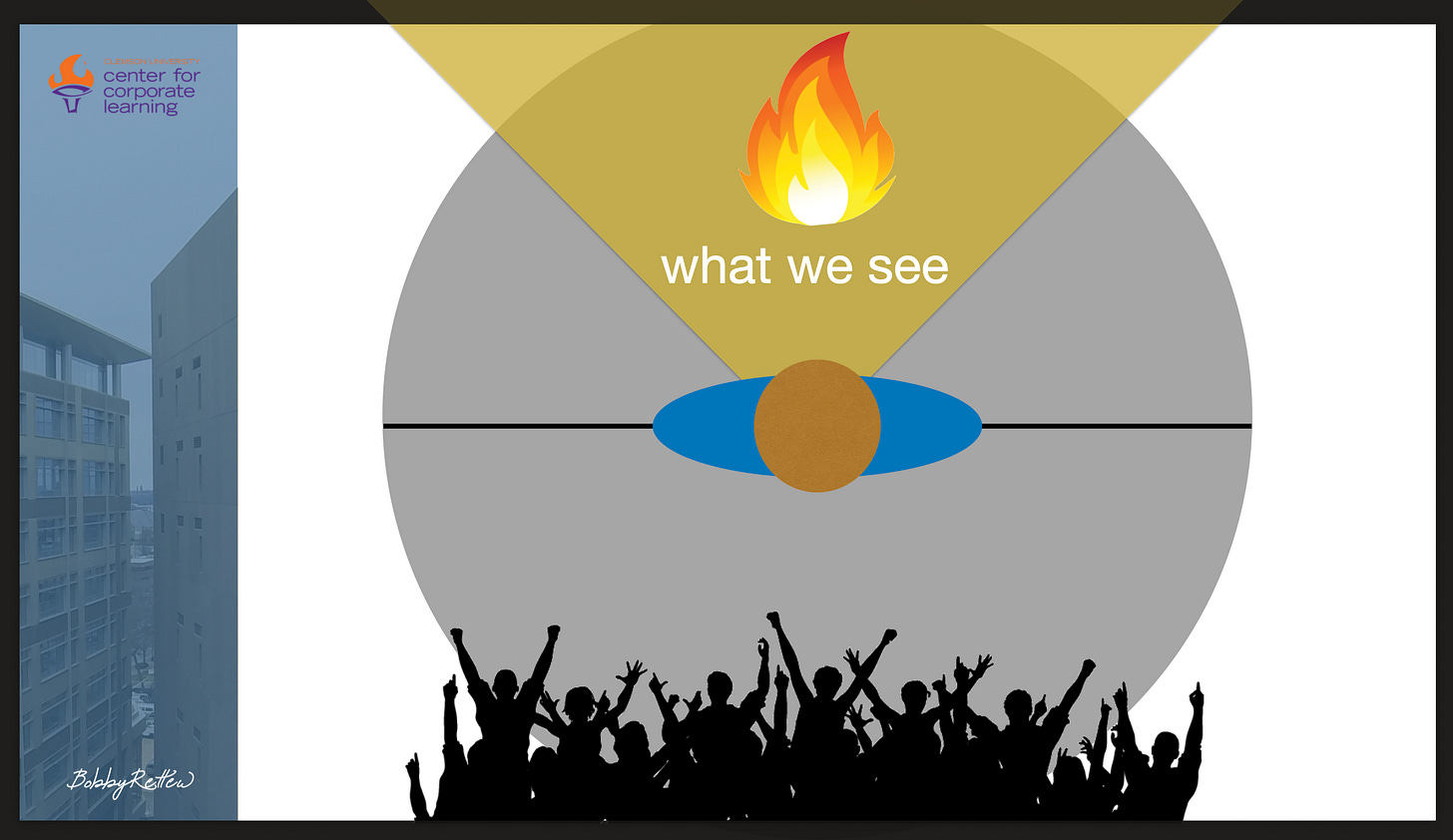

For many years, I’ve been teaching and leading professional development seminars and MBA classes on how to integrate storytelling into business communication and strategy. One slide I always use looks like the image above. It represents a simple but powerful idea I return to again and again: great storytelling is not just about showing what happened right in front of us. It’s about helping an audience see why it matters—to bring them into the emotional and ethical context behind the story.

I call it the difference between action and reaction. Most communicators—and honestly, most of us as humans—are drawn to the action. We point our cameras toward the fire, toward the spectacle, toward whatever’s burning bright enough to capture attention. But the real story often lives 180 degrees away, in the reaction—in the faces watching the fire, in the people feeling its heat, in the voices responding to what that fire means.

That’s where empathy lives. That’s where transformation begins.

Over years of practice, research, and teaching, I’ve come to believe that this principle—turning from the obvious action to the deeper human reaction—is at the heart of great storytelling. It’s also the reason why the funeral sequence in 12 Years a Slave (2013), directed by Steve McQueen, continues to move me every time I see it.

The Fire and the Faces

In this moment, Solomon Northup (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor) stands among a group of enslaved people gathered to bury one of their own…a man who has collapsed and died under the brutal weight of labor in the cotton fields. The camera begins with a wide shot: the burial site, the mourners, the somber landscape. It captures the event…the “fire,” the visible action.

Then, slowly, the camera begins to move closer. It shifts focus from what happened to who is there. We begin to see faces: sorrowful, weary, strong. The sound of singing begins to rise “Roll, Jordan, Roll.” The camera settles on Solomon’s face. He stands silent, shoulders heavy, eyes distant. His lips tremble. And then, almost unwillingly, he begins to sing.

McQueen holds the shot. There are no quick cuts, no camera tricks, no external score guiding our emotion. He lets us sit in the discomfort and the grace of that moment. What we’re watching is not just a man singing…it’s a man rediscovering his humanity. The camera’s slow movement inward mirrors Solomon’s emotional movement from detachment to connection, from survival to belonging.

Went down to the river Jordan,

where John baptized three.

Well, I walked to the devil in hell,

sayin’ John ain’t baptized me.I say: Roll, Jordan, roll,

Roll, Jordan, roll.

My soul arise in heaven, Lord,

for the year when Jordan roll.

The Song as Image, the Moment as Transformation

The man being buried (sometimes identified as Uncle Abram in historical notes) dies from exhaustion, but his death represents more than one man’s loss. McQueen shows us that under slavery, no death was natural. Each death was the result of a system designed to break bodies and spirits. The funeral scene becomes a communal act of mourning, remembrance, and resistance.

The song “Roll, Jordan, Roll” has deep roots in African American spiritual tradition. Originally a hymn by Charles Wesley in 1780, it was later reinterpreted by enslaved Africans in the American South and documented in Slave Songs of the United States (1867). For those who sang it, the River Jordan symbolized more than baptism…it represented the crossing from bondage to freedom, from suffering to deliverance.

When McQueen and composer Hans Zimmer chose this song, they did so intentionally. They used it diegetically…meaning the music comes from the world of the story itself, sung by the characters rather than laid over the top. The power of the scene isn’t in the score; it’s in the breath, the rhythm, the communal voice. It’s in the reaction.

As the song swells, Solomon’s transformation takes shape. Up until this point, his survival has depended on emotional detachment. His “fire” has been endurance. But as he begins to sing, his “reaction” becomes his rebirth. He reclaims his connection to the community around him…and to himself.

The Midpoint: Professor Sean Gaffney’s Offer of Grace

According to Professor Sean Gaffney’s Event Points framework, this moment represents the story’s Midpoint:

“A major event at the center of the plot that alters the Quest of the Central Character either through an amplification or redirection of Want… the first time the character embraces the quality they need to become complete.”

This is exactly what we see in Solomon. His “want” shifts…from simple survival to belonging, from silence to voice. This is his offer of grace: to stay isolated in despair or to open himself to communion, song, and shared humanity.

By singing, he accepts grace.

From that point forward, the story’s emotional current changes. Solomon’s actions carry a new depth…a kind of internal resistance rooted not in defiance, but in identity. The man who was stripped of his name begins to recover his soul.

Image Systems and the Language of the Senses

Sean Gaffney often reminds us that imagery is meaning, not decoration. Visuals describe; images evoke. In this scene, McQueen builds an image system that engages every sense:

Water (the Jordan): a symbol of deliverance, baptism, and freedom.

Earth (the burial ground): mortality, humility, and the weight of history.

Circle (the mourners): community, solidarity, eternity.

Voice (the song): resurrection, defiance, and collective hope.

Each image repeats and deepens across the film…what Robert McKee calls an image system, a network of symbols that accumulates meaning over time. McQueen’s choice to hold the camera, to let the sound of real voices fill the space, creates what Gaffney describes as “compressed communication”…a single visual and auditory moment that carries layers of emotion, history, and subtext.

Beyond Sight: Sensory Imagery

Gaffney also teaches that true imagery goes beyond what we see…it engages all the senses. In this scene, you can almost feel the heat of the sun and smell the turned earth. The rhythm of the clapping and the pulse of the song reach into our own bodies. The image becomes tactile. It doesn’t just play on the screen; it vibrates through us.

That’s what makes it unforgettable.

Brenda Laurel once wrote that the best theater makes us forget we are merely observers…that we become participants in the story. Watching Solomon join the song, I didn’t feel like I was observing him. I felt like I was standing beside him, singing, mourning, believing. For those few moments, the boundary between screen and audience disappeared.

Why It Moves Me

This scene embodies everything I teach about storytelling. It reminds me that to truly connect with an audience, we must look beyond the fire (beyond the spectacle) and pay attention to the human reaction. The event might grab attention, but the reaction holds meaning.

When Solomon begins to sing, he’s not just reacting to death; he’s reclaiming life. The camera doesn’t show us something happening to him…it lets us feel something happening within him. That’s imagery at its highest form.

For me, this isn’t just a film scene. It’s a reminder of how we as communicators (whether filmmakers, business leaders, teachers, or writers) are called to turn our lens toward empathy. We’re not just observers of the world’s fires; we’re witnesses to the light reflected in the human face.

After years of practice, research, and teaching, I’ve learned this simple truth: powerful imagery doesn’t just show the fire…it shows the people illuminated by its light.

Works Cited

12 Years a Slave. Directed by Steve McQueen, performances by Chiwetel Ejiofor, Michael Fassbender, and Lupita Nyong’o, Regency Enterprises, Plan B Entertainment, and River Road Entertainment. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2013.

Laurel, Brenda. Computers as Theatre. Addison-Wesley, 1991.

Allen, William Francis, et al., editors. Slave Songs of the United States. A. Simpson & Co., 1867, pp. 12–13. “Roll, Jordan, Roll.”

Godfrey, Alex. “12 Years a Slave: Steve McQueen on Using Spirituals and Sound to Portray Humanity.*” The Guardian, 2 Jan. 2014, www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jan/02/steve-mcqueen-12-years-a-slave-music-interview. Accessed 5 Oct. 2025.